Renal Dosing Calculator

Antibiotic Renal Dosing Calculator

This calculator estimates creatinine clearance (CrCl) using the Cockcroft-Gault equation to help determine appropriate antibiotic dosing for patients with kidney impairment.

Calculation Results

Dosing Guidance

When someone has kidney disease, giving them the same antibiotic dose as a healthy person isn’t just ineffective-it can be dangerous. Too much of certain antibiotics builds up in the body when the kidneys can’t clear it, leading to hearing loss, nerve damage, or even organ failure. On the flip side, giving too little means the infection won’t get treated, and the patient could die. This isn’t theoretical. In hospitals across the U.S., renal dosing of antibiotics saves lives-but only when done right.

Why Renal Dosing Matters More Than You Think

About 1 in 7 adults in the U.S. has chronic kidney disease (CKD), and that number is rising. Globally, over 850 million people live with some level of kidney impairment. In hospitals, nearly 1 in 4 antibiotic-related adverse events happen in these patients. That’s not a coincidence. Antibiotics like vancomycin, cefazolin, and ampicillin/sulbactam leave the body mostly through the kidneys. If those kidneys are weak, the drugs pile up. Studies show that when dosing isn’t adjusted, death risk jumps by nearly 30% in pneumonia patients and over 20% in those with urinary or abdominal infections.It’s not just about being cautious. It’s about balance. You need enough drug to kill the bacteria, but not so much that it poisons the patient. And that balance changes with every patient’s kidney function.

How Doctors Measure Kidney Function for Dosing

The gold standard isn’t blood creatinine alone. It’s creatinine clearance (CrCl), which estimates how well the kidneys filter waste. The most widely used formula is the Cockcroft-Gault equation. It uses age, weight, sex, and serum creatinine to calculate CrCl:CrCl = [(140 − age) × weight (kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)] × 0.85 (if female)

Many hospitals still rely on this 1976 formula because it’s accurate for dosing purposes-even though newer equations like MDRD and eGFR are used for general kidney staging. Why? Because eGFR overestimates clearance in patients with low muscle mass or obesity. And in antibiotic dosing, overestimation means underdosing, which leads to treatment failure.

Here’s how CrCl levels are typically grouped:

- Normal: CrCl >50 mL/min

- Mild impairment: CrCl 31-50 mL/min

- Moderate impairment: CrCl 10-30 mL/min

- Severe impairment or dialysis: CrCl <10 mL/min

These aren’t just numbers. They directly change how much drug a patient gets-and how often.

How Antibiotic Doses Change Based on Kidney Function

Not all antibiotics behave the same. Some are very forgiving. Others have a razor-thin safety margin. Here’s what happens with common ones:- Ampicillin/sulbactam: Standard dose is 2 grams every 6 hours. But if CrCl is below 15 mL/min? Cut it to 2 grams every 24 hours. Go too high, and you risk seizures. Go too low, and the infection spreads.

- Cefazolin: Usually 1-2 grams every 8 hours. In severe kidney disease, it drops to 500 mg-1 gram every 12-24 hours. This drug has a wide safety margin, so underdosing is more dangerous than overdosing-but many clinicians still reduce it too much.

- Ceftriaxone: No adjustment needed, even in dialysis patients. It’s mostly cleared by the liver. This is one of the few antibiotics you can give at full dose without worrying about kidney function.

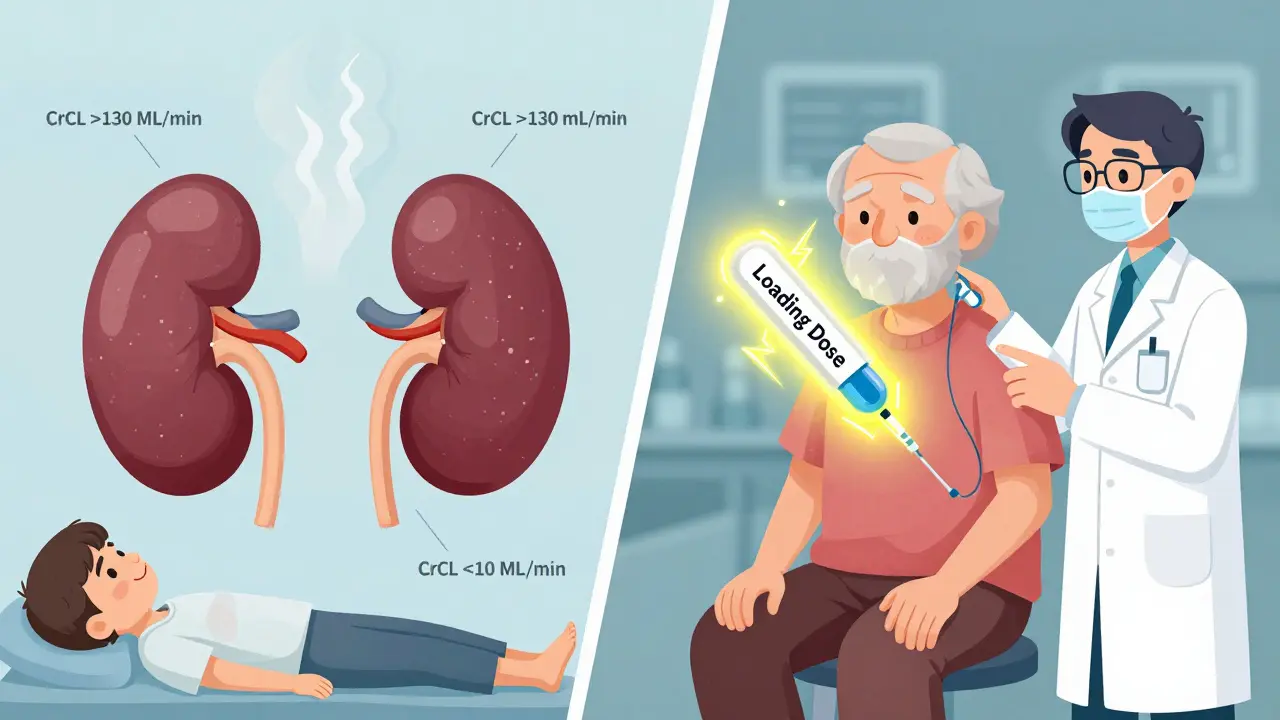

- Vancomycin: Requires a loading dose (25-30 mg/kg) even in kidney failure. Then maintenance doses are spaced out. Skipping the loading dose means the drug takes days to reach therapeutic levels-time the infection doesn’t have.

And then there’s the twist: augmented renal clearance. Some patients-especially young, trauma, or sepsis patients-have kidneys that work too well. CrCl can exceed 130 mL/min. In these cases, standard doses may be too low. For piperacillin/tazobactam, some guidelines recommend 2 grams every 4 hours instead of every 6 or 8. This is often missed in hospital protocols.

Where Guidelines Clash-and Why It’s Dangerous

You’d think there’d be one clear set of rules. But there isn’t. Different institutions use different guidelines, and they often contradict each other.Take clarithromycin. UNMC says: if CrCl is below 30 mL/min, give 500 mg once daily. Northwestern Medicine says: reduce it if CrCl is below 50 mL/min. That’s a 20-point difference in when you start adjusting. One patient could get two different doses depending on which hospital they walk into.

Even worse: acute kidney injury (AKI). Many patients develop sudden kidney failure during hospitalization. Their CrCl drops fast-but it might bounce back in 48 hours. Most guidelines are written for chronic kidney disease, not AKI. So when a patient’s kidney function starts recovering, they’re still on a low dose. That leads to treatment failure. Studies show this increases the risk of infection relapse by 34%.

And then there’s CRRT (continuous renal replacement therapy)-used in ICU patients. Only Northwestern Medicine’s 2025 guidelines include specific dosing for newer antibiotics like ceftazidime-avibactam during CRRT. Others don’t mention it at all. That’s a gap that can cost lives.

What Goes Wrong in Real-World Practice

The science is clear. The problem? Execution.- 63% of physicians misestimate CrCl using Cockcroft-Gault. Many forget to use ideal body weight in obese patients. Some plug in serum creatinine without converting units.

- 78% of dosing errors happen with oral antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin, for example, is often given at 500 mg every 12 hours-even when CrCl is between 10-30 mL/min, where it should be 250 mg every 12 hours.

- Pharmacists report 41% of confusion comes from conflicting guidelines. One hospital says give ampicillin/sulbactam every 24 hours in severe CKD. Another says every 48 hours. Which is right? No one agrees.

And here’s the quiet killer: no loading dose. For time-dependent antibiotics like vancomycin or daptomycin, the first dose sets the tone. If you skip it because the patient has kidney disease, you delay effectiveness by days. That’s not safe-it’s negligent.

Solutions That Actually Work

The good news? We know how to fix this.- Standardize on one guideline. 72% of academic hospitals use KDIGO. It’s the most comprehensive, updated, and evidence-based. If your hospital uses it, you’re ahead of the curve.

- Use electronic alerts. 89% of U.S. hospitals now have EHR alerts that pop up when a drug is ordered for a patient with low CrCl. These reduce errors by over 50%.

- Bring in pharmacists. Pharmacist-led dosing teams cut antibiotic-related adverse events by 37%. They check every dose, verify calculations, and catch the 29% of cases where body weight was misused.

- Train staff on Cockcroft-Gault. Don’t assume everyone knows how to use it. Run a 15-minute module every quarter. Practice with real cases. Make it part of orientation.

And don’t forget: loading doses matter. Always give them when indicated-even if the patient is on dialysis. Don’t wait for approval. Document it. Justify it. It’s standard of care.

The Future of Renal Dosing

The field is changing fast. KDIGO is updating its guidelines in 2025 to finally separate AKI from CKD. The FDA now requires renal dosing studies for every new antibiotic. The European Medicines Agency does too.Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM)-measuring actual drug levels in blood-is growing. Right now, 38% of academic hospitals use it for vancomycin and aminoglycosides. By 2027, that’ll be over 65%. AI tools are being piloted in 17% of U.S. teaching hospitals to predict optimal doses based on CrCl, weight, age, and infection type.

And soon, we may see urinary biomarkers that tell us not just how well the kidneys are filtering now-but how fast they’re recovering. Imagine an antibiotic dose that automatically adjusts as kidney function improves. That’s not science fiction. It’s coming.

For now, the rules are simple: know the patient’s CrCl. Know the drug. Adjust the dose. Never skip the loading dose. And when in doubt, call the pharmacist.

What is the most important factor in renal dosing of antibiotics?

The most important factor is accurately estimating creatinine clearance (CrCl). Using the Cockcroft-Gault equation with correct inputs-especially ideal body weight in obese patients-is critical. Misestimating CrCl leads to underdosing (treatment failure) or overdosing (toxicity). Even small errors can have life-or-death consequences.

Do all antibiotics need dose adjustments in kidney disease?

No. About 60% of commonly used antibiotics require adjustment, but 40% do not. Drugs like ceftriaxone, linezolid, and metronidazole are cleared mainly by the liver or have wide therapeutic margins, so they don’t need dose changes. Always check the specific drug’s profile-don’t assume all antibiotics behave the same.

Should I reduce the dose for a patient with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Not always. AKI can be temporary. Many patients recover kidney function within 48 hours. Reducing doses too early can lead to treatment failure. For antibiotics with a wide therapeutic index (like cefazolin), consider giving full doses initially and adjusting only if kidney function doesn’t improve. Always reassess CrCl daily.

Is it safe to give a loading dose to someone with severe kidney disease?

Yes-for many antibiotics, it’s essential. Vancomycin, daptomycin, and some beta-lactams require a loading dose to reach effective levels quickly. The loading dose is not reduced for kidney disease, even in dialysis patients. Only the maintenance dose is adjusted. Skipping the loading dose delays treatment and increases mortality risk.

Why do different hospitals have different dosing rules?

Because guidelines aren’t standardized. UNMC, Northwestern Medicine, KDIGO, and others have slight differences in recommendations, especially for borderline cases or newer drugs. Some include CRRT dosing, others don’t. Some adjust for augmented renal clearance, others ignore it. The best practice is to adopt one authoritative source (like KDIGO) and stick to it across your institution.

Jonathan Noe

February 10, 2026 AT 17:09Gabriella Adams

February 11, 2026 AT 10:09Luke Trouten

February 12, 2026 AT 12:16steve sunio

February 12, 2026 AT 19:47Robert Petersen

February 14, 2026 AT 11:33Ojus Save

February 16, 2026 AT 06:51Steve DESTIVELLE

February 16, 2026 AT 22:53Stephon Devereux

February 17, 2026 AT 12:22alex clo

February 18, 2026 AT 00:53