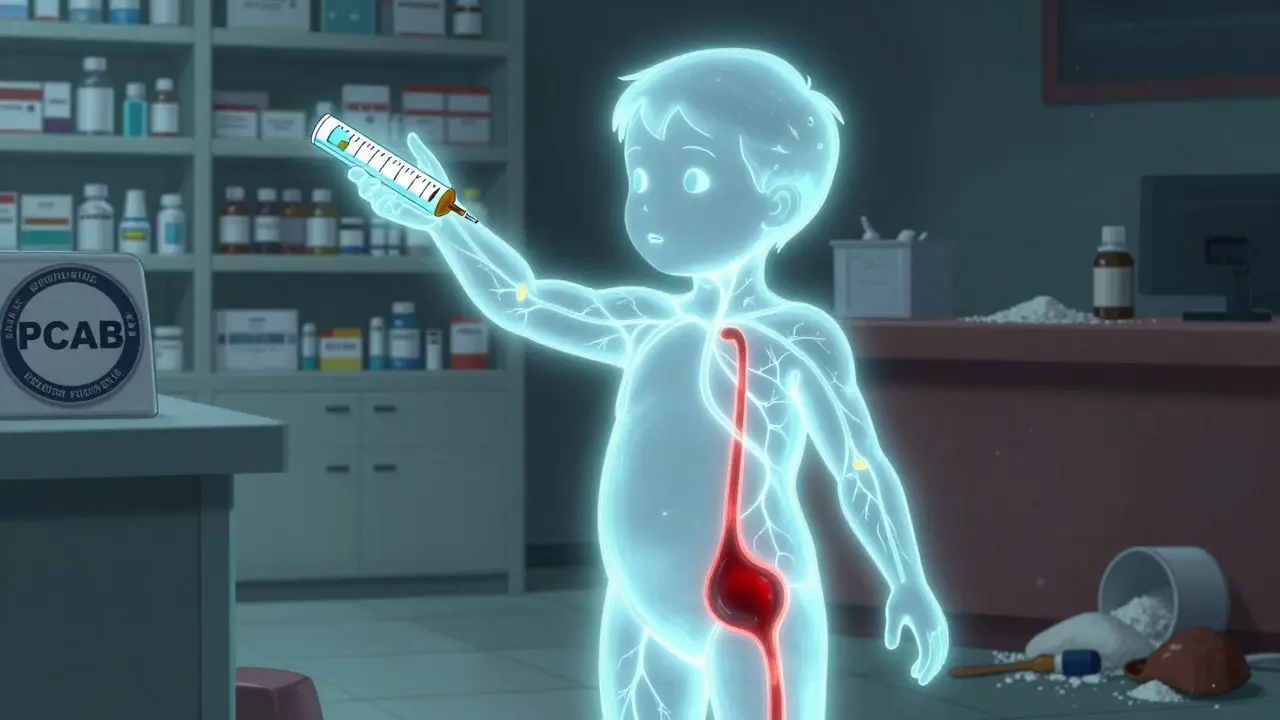

When your child needs a medicine that doesn’t come in a store-bought bottle-maybe they can’t swallow pills, are allergic to dyes, or need a tiny dose that’s not made for kids-you might hear the word compounded. It sounds technical, but it’s just a custom-made version of a drug, mixed by a pharmacist to fit your child’s exact needs. It’s not magic. It’s pharmacy. But it’s also risky if not done right.

What Exactly Is a Compounded Medication?

A compounded medication is made from scratch by a licensed pharmacist using raw ingredients. Unlike regular drugs you buy at CVS or Walgreens-which are mass-produced, tested, and approved by the FDA-compounded drugs are not reviewed by the FDA for safety or effectiveness. That’s not because they’re bad. It’s because they’re made for special cases. For children, this often means:- Liquid forms instead of pills for kids who can’t swallow

- Flavorings like strawberry or bubblegum to hide bitter tastes

- Sugar-free versions for diabetic kids

- Alcohol- and dye-free formulas for sensitive children

- Very small doses of strong medicines like morphine or fentanyl, diluted to safe levels

Why Are Compounded Medications Risky for Kids?

Children aren’t small adults. Their bodies process medicine differently. A dose that’s safe for a 150-pound teen could be toxic for a 20-pound toddler. And because compounded meds are made one at a time, human error creeps in. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that 14% to 31% of pediatric medication errors involve compounded drugs. Most of these are dosing mistakes. One parent shared online that their 8-year-old ended up in the ER after a compounded thyroid pill was only 60% as strong as it should’ve been. Another child nearly died when a compounded IV solution was mixed too strong. The 2012 fungal meningitis outbreak killed 64 people and sickened nearly 800 after contaminated compounded spinal injections were given. That wasn’t a rare accident. It was a system failure. And now, with the rise of compounded versions of drugs like semaglutide and tirzepatide, the FDA has recorded over 900 adverse events-including 17 deaths-since the start of 2024. Pediatric patients are showing up in emergency rooms with vomiting, nausea, and acute pancreatitis from these errors.When Should You Even Consider a Compounded Medication?

The FDA says it clearly: only use compounded drugs when there’s no FDA-approved alternative. Before you agree to a compounded prescription, ask:- Is there a commercial version of this drug that comes in liquid form?

- Can the pill be crushed and mixed with food safely?

- Is there a pre-mixed, unit-dose syringe available for IV meds?

How to Find a Safe Compounding Pharmacy

Not all pharmacies that compound are equal. There are over 7,200 compounding pharmacies in the U.S., but only about 1,400 are accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB) or the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP). Here’s how to check:- Ask your doctor or pharmacist for the name of the pharmacy they use.

- Go to pcabaccreditation.org or nabp.pharmacy and search by name or location.

- Verify they’re licensed by your state’s pharmacy board.

- Ask if they use gravimetric analysis (a precise weighing method) for sterile preparations.

What to Ask Before You Leave the Pharmacy

Never walk away without these three questions:- What’s the exact concentration? Is it 5 mg/mL? 10 mg/mL? Write it down. Many errors happen because parents think the bottle says “10 mg” when it actually says “10 mg per 5 mL.”

- How should I store it? Some need refrigeration. Others expire in 14 days. Using an expired or improperly stored compound can be dangerous.

- Can I get a written dosing chart? Ask for the dose in milliliters (mL) and a syringe marked in mL-not teaspoons or tablespoons. Household spoons vary wildly in size.

Double-Check Everything

Always verify the dose with your child’s doctor and the pharmacist. Don’t assume they’re on the same page. If your child is getting a compounded IV medication, ask if the pharmacy does a second independent check before dispensing. The ISMP recommends this for every pediatric sterile compound. It’s not optional-it’s life-saving. Also, check the label. Does it say “For External Use Only”? That’s a red flag if it’s meant to be swallowed. Is there a lot of air in the vial? That could mean it was improperly filled.Technology Can Save Lives-But It’s Not Used Enough

There’s a tool called gravimetric analysis that uses ultra-precise scales to measure ingredients down to the milligram. It’s used in hospitals for neonatal ICUs. It cuts dosing errors by 75%. Yet only 7.7% of U.S. hospitals use it. Why? Because it costs $25,000 to $50,000 per station. It requires training. It takes longer to prepare a dose. Small pharmacies, especially in rural areas, can’t afford it. That’s why kids in those areas are at higher risk. Advocates like the Emily Jerry Foundation are pushing for “Emily’s Law”-state legislation that would require gravimetric verification for all pediatric compounded sterile drugs. As of April 2025, 28 states have introduced such bills.

What to Do If Something Feels Wrong

Your child starts vomiting after taking a new compounded medicine? Gets unusually sleepy? Has a rash? Doesn’t seem like themselves? Stop the medication. Call your pediatrician. Call the pharmacy. And report it. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) collects these reports. If you don’t report it, they won’t know it’s happening. One report might not change anything. But 100 reports? That’s how problems get fixed. You can report online at fda.gov/medwatch or by calling 1-800-FDA-1088.What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is stepping up inspections of compounding pharmacies. In May 2025, they warned that some pharmacies are exploiting drug shortages to make and sell compounded versions-even after the shortage is over. New pediatric-specific safety metrics are coming from the ISMP in late 2025. These will help hospitals and pharmacies track their error rates and improve. And more parents are speaking up. Online forums like Reddit’s r/pediatrics are full of stories from families who’ve been burned by bad compounding. Their voices are pushing change.The Bottom Line

Compounded medications can be a lifeline for children with no other options. But they’re not safer just because they’re custom-made. They’re riskier because they’re handmade. If you’re asked to use one:- Make sure it’s truly necessary.

- Use only an accredited pharmacy.

- Get the concentration in writing.

- Verify the dose with two professionals.

- Store it correctly.

- Watch for side effects.

- Report anything unusual.

Windie Wilson

January 12, 2026 AT 17:12Amanda Eichstaedt

January 13, 2026 AT 12:37Abner San Diego

January 13, 2026 AT 14:56Eileen Reilly

January 15, 2026 AT 05:19Monica Puglia

January 15, 2026 AT 19:54Cecelia Alta

January 17, 2026 AT 06:52steve ker

January 18, 2026 AT 01:50George Bridges

January 19, 2026 AT 12:00Rebekah Cobbson

January 19, 2026 AT 13:09Audu ikhlas

January 21, 2026 AT 08:21TiM Vince

January 21, 2026 AT 23:27