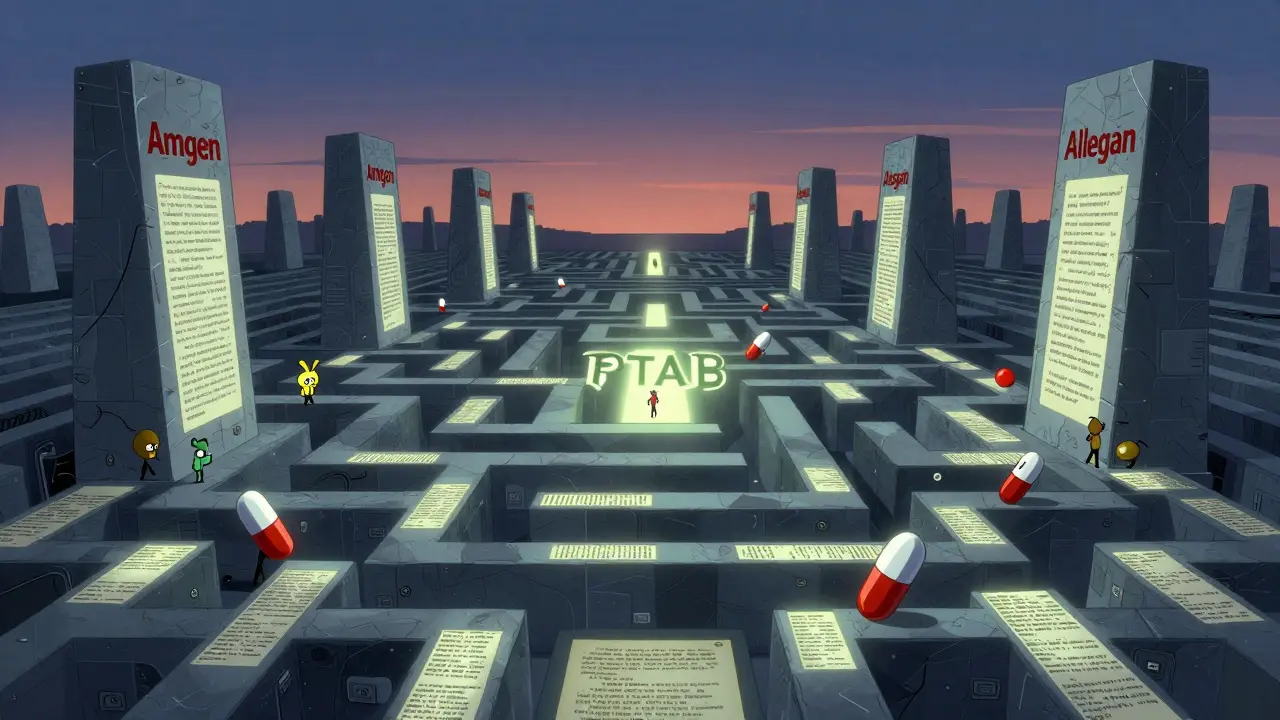

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, you’d expect a generic version to hit the market quickly-cheaper, just as effective, and widely available. But that’s not always what happens. Behind the scenes, a complex web of court rulings, patent filings, and regulatory rules determines whether a generic drug can enter the market at all. These aren’t abstract legal debates. They directly affect how much you pay for insulin, blood pressure meds, or cancer treatments. The key battleground? generic patent case law.

How Generic Drugs Get Stuck in Court

The system was designed to balance innovation and access. In 1984, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to let generic manufacturers copy brand-name drugs without repeating expensive clinical trials. In return, they had to respect valid patents. The process starts when a generic company files an ANDA-Abbreviated New Drug Application-with the FDA. But here’s the twist: they must certify whether they believe the brand’s patents are invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. That’s called a Paragraph IV certification. And when they do that? The brand company can sue. That lawsuit triggers a 30-month automatic stay, blocking the generic from launching-even if the FDA has approved it. This isn’t rare. In 2023, over 2,100 of these lawsuits were filed in the U.S. alone. Most involve small molecule drugs-things like pills for cholesterol or diabetes. But increasingly, they’re targeting biologics: complex, injectable drugs made from living cells. These are harder to copy, and the patents around them are more fragile-and more fiercely defended.Landmark Ruling: Amgen v. Sanofi (2023)

One case changed everything for biologic patents. Amgen held a patent covering a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs called PCSK9 inhibitors. They claimed their patent covered millions of possible antibody variations, but only actually made and tested 26. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously: that’s not enough. You can’t claim ownership over something you haven’t actually invented or described in enough detail. The court said the patent failed the legal requirement of “enablement”-meaning, someone else couldn’t replicate it based on the patent alone. This decision sent shockwaves through the industry. Before Amgen, companies could write broad patents covering huge ranges of molecules, then sue anyone who came close. After Amgen, those patents started falling apart. Generic makers saw it as a win. But brand companies panicked. If broad biologic patents are harder to defend, what happens to the next generation of cancer drugs or autoimmune treatments? The ruling didn’t kill innovation-it just demanded more precision. Now, patent lawyers have to write narrower, more detailed claims. And generic companies? They’re finding more opportunities to challenge patents before they even file their ANDA.Another Turning Point: Allergan v. Teva (2024)

While Amgen made it harder to get broad patents, Allergan v. Teva made it harder to knock them out. Allergan held a patent on a nasal spray for allergies. Teva challenged it, arguing another patent-filed later but set to expire sooner-should invalidate the original. The Federal Circuit said no. A later-filed patent can’t be used to kill an earlier one just because it expires first. The court emphasized that patent rights are granted based on when they were filed, not when they run out. This decision strengthened brand companies’ ability to build “patent thickets”-stacking multiple patents around a single drug, each covering a different aspect: the formula, the delivery device, the method of use. Even if one patent expires, another might still block generics. Critics call it gaming the system. Supporters say it’s just protecting legitimate investment. Either way, it means generics now face more hurdles. A single drug might have 10 or more Orange Book-listed patents. Each one is a potential lawsuit.

The Labeling Trap: Amarin v. Hikma (2024)

Here’s a sneaky tactic brand companies are using: suing over what’s written on the generic’s label. Amarin made a heart drug approved only for one use-lowering triglycerides in very high-risk patients. Hikma made a generic version and labeled it the same way, but only marketed it for a different, off-label use that was already common. Amarin sued, claiming Hikma’s marketing materials “induced” doctors to use it for the approved use. The court agreed. Even though Hikma didn’t claim the approved use on its label, the court found their promotional materials crossed the line. This is a big deal. Generic manufacturers now have to be hyper-careful about every word in their ads, websites, and sales pitches. Even if the label says “for use X,” if the sales rep says “this works for use Y too,” they can be sued for induced infringement. In 2023, 63% of branded companies’ induced infringement claims succeeded. It’s not about the drug-it’s about the message.How the System Favors Big Players

The rules sound fair on paper. But in practice, they favor deep pockets. A single Hatch-Waxman lawsuit can cost $6-8 million. Small generic companies often can’t afford to fight. That’s why 87% of the top 100 generic manufacturers now have full-time patent litigation teams. Meanwhile, big pharma spends hundreds of millions annually on legal teams and lobbying. Firms like Fish & Richardson and Covington & Burling dominate this space-they’ve handled nearly 70% of all major cases in the past five years. The 180-day exclusivity period for the first generic to file a Paragraph IV challenge sounds like a reward. But it’s not always a win. Sometimes, multiple companies file on the same day. Sometimes, the first filer gets bogged down in litigation and never launches. Sometimes, the brand company settles with the first filer, paying them to delay entry-what’s called a “pay-for-delay” deal. Those deals are now illegal under FTC rules, but they still happen in disguised forms: licensing deals, distribution agreements, or side payments.

Henry Sy

January 14, 2026 AT 20:00Jason Yan

January 16, 2026 AT 19:02shiv singh

January 18, 2026 AT 12:40Robert Way

January 19, 2026 AT 23:07Vicky Zhang

January 21, 2026 AT 09:55Alvin Bregman

January 22, 2026 AT 02:15Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 22, 2026 AT 23:22Anna Hunger

January 24, 2026 AT 02:42Sarah Triphahn

January 25, 2026 AT 15:30Allison Deming

January 26, 2026 AT 01:21Susie Deer

January 26, 2026 AT 21:16TooAfraid ToSay

January 27, 2026 AT 22:18