When a doctor prescribes a medication like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin, the difference between a life-saving dose and a dangerous one can be razor-thin. These are NTI drugs - narrow therapeutic index drugs - and they’re not like most other medications. A 10% change in blood levels might mean the drug stops working, or worse, causes serious harm. That’s why the FDA treats them differently when approving generic versions. Standard bioequivalence rules don’t cut it here. The agency has built a whole extra layer of testing to make sure generics are truly safe to swap in.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

The FDA defines NTI drugs based on hard data, not guesswork. In 2022, they used pharmacometric analysis to set a clear cutoff: if a drug’s therapeutic index is 3 or lower, it’s classified as NTI. That means the smallest dose that works is no more than three times smaller than the dose that causes toxicity. Out of 13 drugs studied, 10 fell at or below this line. Drugs like carbamazepine, cyclosporine, lithium, and valproic acid all meet this standard.

But it’s not just about the ratio. The FDA also looks at whether the drug needs regular blood monitoring, if doses are adjusted in small increments (like 5-10 mg), and if the range between the lowest effective and highest safe blood concentration is narrow. If a drug checks those boxes, it’s flagged for stricter rules. The agency doesn’t publish a single public list. Instead, you find NTI status in product-specific guidance documents for each drug. That means if you’re looking at a generic version of tacrolimus, you need to check the FDA’s guidance for tacrolimus - not a master list.

Why Standard Bioequivalence Rules Fail for NTI Drugs

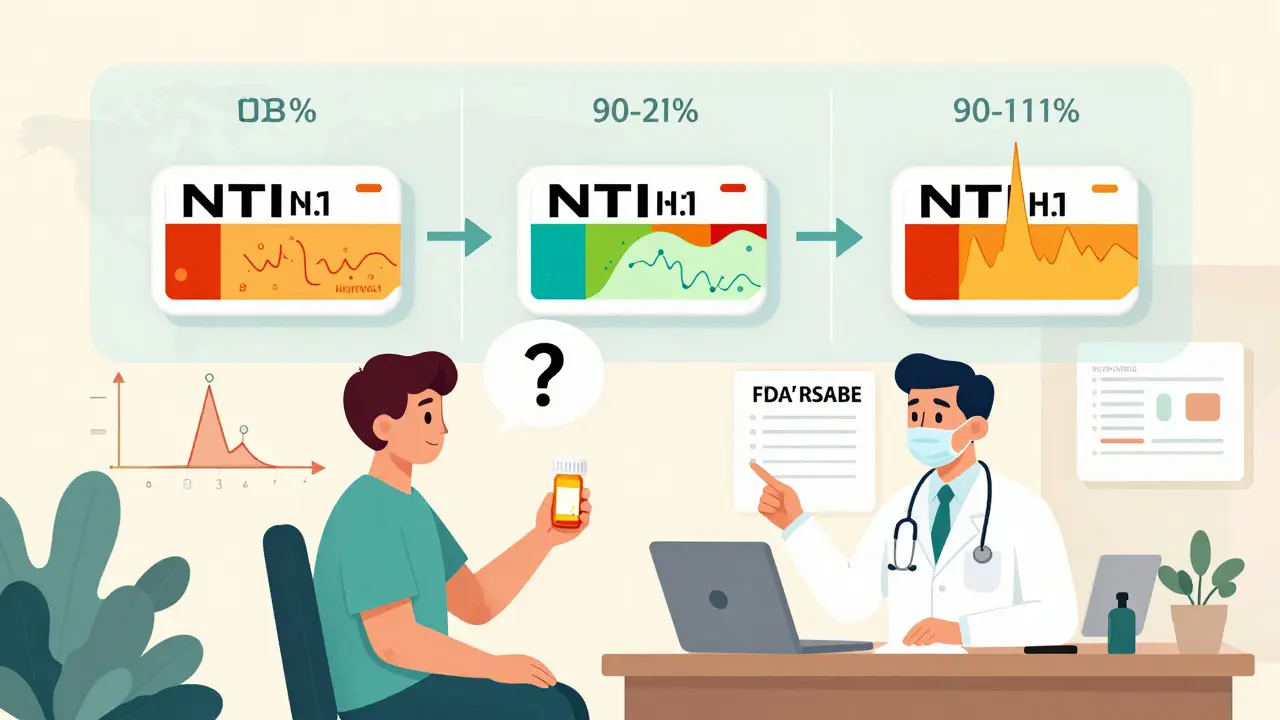

For most generic drugs, the FDA accepts bioequivalence if the generic’s blood levels fall within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s a 45% range. For NTI drugs, that’s far too wide. A 20% drop in concentration could mean a seizure in an epilepsy patient. A 15% spike could cause bleeding in someone on warfarin. In 2010, the FDA’s advisory committee voted 11-2 that the old standard was unsafe for these drugs. They recommended tightening the range to 90% to 111% - a 21% window - and requiring that the average be centered on 100%.

It’s not just about the average, though. The FDA also looks at variability. If the brand-name drug shows a lot of fluctuation in blood levels from person to person, the generic must match that pattern. That’s where scaled bioequivalence comes in. For NTI drugs, the FDA uses a method called RSABE - Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence. It allows slightly wider limits if the brand drug itself is highly variable, but only if the generic’s variability doesn’t exceed the brand’s by more than 2.5 times. Even then, the generic must still pass the tighter 90-111% average limit.

The Two-Part Test for NTI Drug Approval

Generic manufacturers don’t just run one test. They must pass two separate bioequivalence criteria:

- Reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE): The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference must fall within the scaled limits, which are narrower than 80-125% but adjusted based on the brand’s variability.

- Conventional average bioequivalence (ABE): The same 90-111% range must be met without scaling - meaning even if the brand is variable, the generic still has to hit the tighter target.

On top of that, the within-subject variability (how much a person’s own blood levels bounce around) of the generic must not be more than 2.5 times higher than the brand’s. This prevents manufacturers from creating a product that works on average but is wildly inconsistent from dose to dose.

These requirements mean NTI drug studies are more expensive and complex. They require replicate designs - giving the same patient both the brand and generic multiple times - to measure within-person variability accurately. Sample sizes are larger, and the statistical analysis is more demanding. A generic drug that passes for a regular medication might fail outright for an NTI drug.

Quality Control Is Even Tighter

It’s not just about how the drug behaves in the body. The FDA also demands stricter quality control for NTI generics. For regular drugs, the active ingredient can vary by 90-110% of the labeled amount. For NTI drugs, that range shrinks to 95-105%. That’s half the allowed variation. If a tablet is supposed to contain 10 mg, it can’t be less than 9.5 mg or more than 10.5 mg. For drugs where a 0.5 mg difference can trigger toxicity, this matters.

Manufacturers must also prove batch-to-batch consistency. One batch can’t drift too far from the next. This is especially important for drugs like lithium, where even tiny changes in salt content can affect absorption. The FDA doesn’t just trust the manufacturer’s data - they inspect facilities and review analytical methods to ensure labs can detect these small differences.

Real-World Examples: Tacrolimus, Warfarin, and Phenytoin

Tacrolimus, used after organ transplants, is a classic NTI drug. Studies show that generic versions can meet the 90-111% bioequivalence standard and still be safe and effective in transplant patients. But here’s the catch: two generics that both pass FDA standards might not be bioequivalent to each other. One might be closer to the brand, while another is at the edge of the 90-111% range. That’s why switching between different generic brands can sometimes cause issues - even if each one is FDA-approved.

Warfarin, a blood thinner, has similar challenges. Studies have shown that patients switched between different generic versions sometimes need dose adjustments. The FDA acknowledges this, but says the problem isn’t with the approval standard - it’s with how substitutions are managed in clinics. Phenytoin, an antiepileptic, has a long history of substitution concerns. Even though studies show most generics meet the NTI criteria, some neurologists still avoid switching patients because of anecdotal reports of breakthrough seizures.

The FDA’s position is clear: if a generic passes their NTI standards, it’s therapeutically equivalent. But they also admit that real-world experience - especially with antiepileptics - has created lingering doubt among doctors and patients. That’s why some states still require patient consent before substituting an NTI generic, even when the FDA says it’s safe.

Global Differences and the Road Ahead

The U.S. approach is unique. The European Medicines Agency and Health Canada tend to just tighten the bioequivalence range to 90-111% across the board, without scaling for variability. The FDA’s method is more sophisticated - it accounts for how the brand drug behaves, not just a fixed number. That makes it harder for manufacturers to game the system, but also more complex to understand.

The FDA is working on better harmonizing these standards globally. Right now, a generic approved in the U.S. might not meet Canada’s or Europe’s rules - and vice versa. That creates confusion for patients who travel or for manufacturers trying to sell worldwide.

Also, about 15% of newly approved generic drugs in 2022 were NTI drugs. That number is rising. As more complex drugs enter the market - especially targeted cancer therapies and immunosuppressants - the need for precise bioequivalence standards will only grow. The FDA is investing in better pharmacometric models and real-world data collection to keep refining its approach.

What This Means for Patients and Providers

If you’re on an NTI drug, you’re not taking a risk by using an FDA-approved generic. The agency’s standards are among the strictest in the world. But you should still be aware: switching between different generic brands might require monitoring. Don’t assume all generics are identical. If you notice changes in how you feel after a switch - even if it’s a small thing like increased fatigue or a slight change in lab results - talk to your doctor. Blood tests may be needed.

Pharmacists should know which drugs are NTI and be ready to explain why substitution might require extra caution. Just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s interchangeable without oversight. The FDA says they’re equivalent - but the system works best when everyone understands the stakes.

For prescribers, the message is simple: trust the FDA’s approval, but don’t ignore clinical judgment. If a patient has been stable on a specific brand or generic for months, don’t switch unless necessary. And if you do switch, monitor closely. The science supports substitution - but medicine is still practiced one patient at a time.

What drugs are considered NTI drugs by the FDA?

The FDA doesn’t publish a single public list, but commonly recognized NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, digoxin, lithium, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, everolimus, and valproic acid. These are identified through product-specific guidance documents based on their therapeutic index (≤3), need for blood monitoring, and narrow safety margin.

Why is the bioequivalence range for NTI drugs tighter than for other drugs?

For NTI drugs, even small changes in blood concentration - as little as 10% - can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. The standard 80-125% range used for most generics is too wide for these medications. The FDA requires a tighter 90-111% range to ensure that generic versions deliver nearly identical exposure, reducing the risk of harm.

Can different generic versions of the same NTI drug be substituted for each other?

Each generic must meet FDA standards individually, but two generics that both pass may not be bioequivalent to each other. For example, Generic A might be very close to the brand, while Generic B is at the edge of the 90-111% limit. Switching between them can cause fluctuations in blood levels, which is why some clinicians avoid multiple substitutions. Always monitor patients when changing between generics.

Do I need to get patient consent before substituting an NTI generic?

Federal law allows substitution of FDA-approved generics, including NTI drugs. But state laws vary. Some states require explicit patient consent or prohibit automatic substitution for NTI drugs. Pharmacists must follow their state’s rules, even if the FDA considers the generic equivalent. Always check local regulations before substituting.

Are generic NTI drugs as safe and effective as brand-name versions?

Yes - if they’ve passed the FDA’s stricter NTI bioequivalence standards. The agency requires tighter quality control (95-105% potency), scaled bioequivalence testing, and lower variability limits. Real-world data shows that generic NTI drugs work as expected in most patients. However, clinical experience with antiepileptics has raised concerns, so ongoing monitoring is recommended, especially during initial substitution.

Mandy Kowitz

January 3, 2026 AT 20:24So let me get this straight - we’re trusting life-or-death meds to pill factories that can’t even spell ‘bioequivalence’ right on the label? And you call this science? 😒

Rory Corrigan

January 5, 2026 AT 14:02It’s not about the numbers. It’s about the silence between the doses. The quiet panic when your hands shake because you don’t know if today’s pill is the one that’ll keep you alive or bury you. We’re not data points. We’re humans with broken systems.

Siobhan Goggin

January 6, 2026 AT 10:30This is exactly why I moved from the US to the UK - at least over here they don’t pretend a 10% swing is ‘safe’ for anything that keeps you breathing. Kudos to the FDA for trying, but the system still feels like a gamble.

Dee Humprey

January 6, 2026 AT 14:50As a pharmacist, I see this every day. Patients switch generics and come back saying ‘I don’t feel right.’ We check labs - levels are technically ‘in range.’ But ‘in range’ doesn’t mean ‘felt the same.’

Always ask: did the patient feel stable before? If yes, don’t fix what isn’t broken. And yes, I document every switch. Always.

Justin Lowans

January 8, 2026 AT 11:08The FDA’s approach to NTI drugs is arguably the most rigorous pharmacometric framework in existence. By coupling scaled bioequivalence with strict within-subject variability limits and potency controls, they’re not just checking boxes - they’re engineering safety into the molecular level.

It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we’ve got. The real challenge lies in communication: clinicians, pharmacists, and patients need to understand that ‘FDA-approved’ doesn’t mean ‘identical,’ it means ‘within scientifically validated tolerances.’

Let’s stop treating bioequivalence like a binary switch and start treating it like a calibrated instrument.

Jason Stafford

January 9, 2026 AT 09:31They’re lying. The FDA doesn’t want you to know that the same labs that approve these generics also get paid by the manufacturers. There’s a revolving door between the agency and Big Pharma. They tightened the range just enough to make it look like they care - but the inspections? The audits? The whistleblower reports? Buried.

My cousin went into a coma after switching generics. The report said ‘no correlation.’ Bullshit. The pill was 96% potency. That’s not a coincidence - it’s a countdown.

Peyton Feuer

January 10, 2026 AT 18:00man i just got switched to a generic for my cyclosporine last month and honestly? felt a little off for a week. not bad, just… weird. tired, kinda dizzy. my doc said ‘it’s fine, levels are good’ but i asked for my old brand back. now i’m fine. maybe it’s placebo, maybe not. but i’m not risking it again.

also lol at the ‘FDA says it’s safe’ thing - if i trusted everything the fda said, i’d be eating aspartame for breakfast.

Cassie Tynan

January 11, 2026 AT 07:13It’s funny how we treat medicine like a spreadsheet when it’s really a living conversation between a body and a molecule. We quantify everything - therapeutic index, variability, confidence intervals - but we forget that patients aren’t test tubes. They’re people who’ve survived, who’ve cried in waiting rooms, who’ve memorized the exact time their pill kicks in.

So yes, the FDA’s standards are brilliant. But the real innovation? Listening when someone says, ‘This doesn’t feel like the same pill.’

That’s not bad science. That’s human science.

John Wilmerding

January 13, 2026 AT 05:08It is imperative to underscore that the regulatory framework governing narrow therapeutic index pharmaceuticals represents a paradigm shift in pharmacovigilance. The integration of reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) with conventional average bioequivalence (ABE) establishes a dual-validation protocol that mitigates both systemic bias and intra-individual variance.

Furthermore, the 95–105% manufacturing tolerance for active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) content constitutes a substantial enhancement over the 90–110% standard applied to non-NTI agents.

While challenges persist regarding inter-generic interchangeability, the evidentiary basis supporting FDA approval remains robust, and clinical vigilance - not skepticism - should guide therapeutic decisions.