When you're managing a chronic condition like high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes, your doctor might give you two or three pills instead of one. That’s not a mistake - it’s a de facto combination. This is when patients take separate generic medications that, together, act like a Fixed-Dose Combination (FDC), even though they’re not packaged or approved as one. It’s legal. It’s common. But it’s not always safe.

What exactly is a de facto combination?

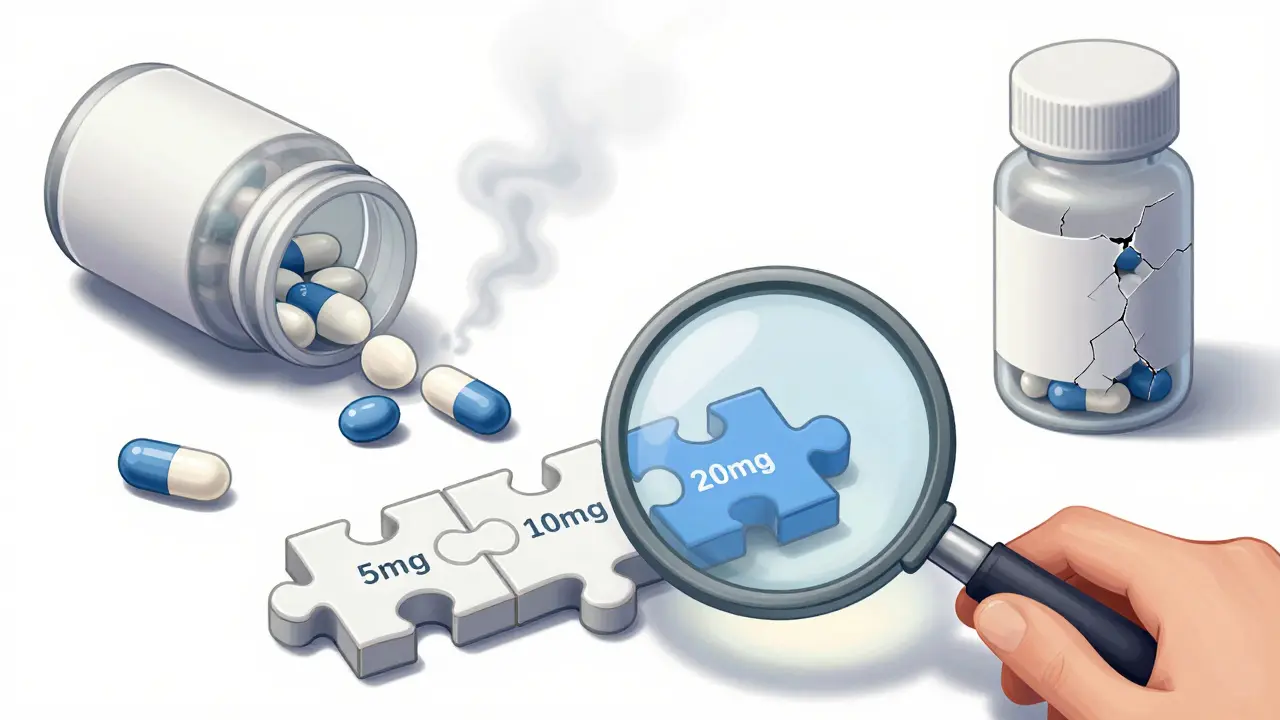

An FDC is a single pill that contains two or more active ingredients in a fixed ratio - like amlodipine and valsartan for hypertension, or metformin and sitagliptin for diabetes. These are rigorously tested by the FDA and EMA to prove they work better together than separately, are stable, and don’t interact dangerously. But when your doctor prescribes those same two drugs as separate pills - say, a 5mg amlodipine tablet and a 160mg valsartan tablet - you’re on a de facto combination. No regulatory review. No joint bioequivalence data. Just two generics, taken at the same time.

This happens because FDCs often come in fixed doses. If you need 10mg of drug A and 80mg of drug B, but the only available FDC has 20mg of A and 160mg of B, your doctor can’t adjust it. So they prescribe the two generics separately. It’s practical. But it’s also a workaround that skips the safety checks built into FDCs.

Why do doctors choose separate generics?

Three big reasons: dosing flexibility, cost, and availability.

First, flexibility. In diabetes, for example, kidney function changes over time. A patient might need 500mg of metformin and 25mg of sitagliptin. But the only FDC available is 1000mg/50mg. That’s too much. Separate generics let the doctor fine-tune each dose. The same applies to elderly patients, those with liver issues, or people on multiple other medications. A one-size-fits-all FDC doesn’t fit everyone.

Second, cost. In the U.S., brand-name FDCs can cost $300 a month. But if both generic components are available, you might pay $15 for metformin and $20 for sitagliptin - $35 total. Even with insurance, copays for FDCs can be higher if the combination isn’t on the preferred list. In countries like India, where FDCs were banned for lacking evidence, separate generics became the default - and sometimes cheaper.

Third, availability. Some FDCs aren’t made at all. For example, there’s no FDA-approved FDC combining lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide in a 20mg/12.5mg ratio - even though many patients need exactly that. So doctors prescribe the two generics. It’s not off-label; it’s just not packaged together.

The hidden risks you might not know about

De facto combinations sound harmless - until something goes wrong.

One major issue is adherence. Every extra pill you take per day reduces your chance of sticking to your regimen. A 2019 study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that each additional pill cut adherence by 16%. Patients on FDCs were 22% more likely to take their meds consistently. Think about it: one pill, once a day. Easy. Two pills, twice a day? You forget. You run out of one. You don’t refill both at the same time. A Reddit user with hypertension wrote: “I switched from a single FDC to separate generics to save $15/month. Now I miss doses because I can’t tell which blue pill is which.”

Another risk is drug interaction and stability. FDCs are tested together - how they dissolve, how they’re absorbed, whether one affects the other. Separate generics? Not necessarily. One generic might be immediate-release; the other, extended. One might have a different filler that alters absorption. The FDA found that 12.7% of generic drugs differ clinically from their reference products. When you combine two, you’re doubling that uncertainty.

And then there’s the lack of safety data. FDCs must prove the combination improves outcomes over monotherapy. De facto combinations? No one’s studied them. The EMA says every FDC must show a “positive benefit-risk profile.” De facto combinations skip that. Dr. Kenneth H. Fye called it a “therapeutic Wild West” in a 2021 JAMA commentary.

When does it make sense - and when doesn’t it?

Not all de facto combinations are bad. Some are necessary.

For example: A 72-year-old with diabetes and stage 3 kidney disease needs metformin at 500mg twice daily and empagliflozin at 10mg once daily. The FDCs available are 1000mg/25mg or 500mg/10mg. Neither fits. So separate generics are the only safe option. In this case, flexibility saves lives.

But here’s where it gets dangerous: when doctors prescribe de facto combinations out of convenience, not need. A 2022 survey of 1,532 U.S. pharmacists found that 72% worried about medication errors from uncoordinated regimens. One common scenario: a patient gets amlodipine from one doctor, lisinopril from another, and hydrochlorothiazide from a third. All generics. All taken at different times. No one checks if the doses add up to something harmful. The result? More ER visits, more confusion, more hospitalizations.

How to manage de facto combinations safely

If you’re on separate generics that make up a combination, here’s how to stay safe:

- Use a pill organizer with color-coded compartments. Don’t rely on memory.

- Sync your refills. Ask your pharmacy to refill all components on the same day.

- Ask your pharmacist if the generics you’re taking have been tested together. Some pharmacies track compatibility.

- Request an FDC if possible. If your doses match an approved combination, ask if switching would be safer and cheaper.

- Keep a written schedule. Include times, doses, and what each pill looks like. Bring it to every appointment.

Some pharmacies now offer services like PillPack (by Amazon) that pre-sort medications into daily packets. They’ve cut adherence errors by 41% for patients on de facto combinations. If your insurance covers it, ask.

The future: smarter combinations

Pharma companies are starting to listen. AstraZeneca just patented a modular FDC system that lets you snap in different dose strengths - like building blocks. It’s still experimental, but it could solve the flexibility problem without sacrificing safety.

The FDA is also moving. In 2023, they warned of 147 adverse events tied to untested combinations. New electronic prescribing systems are being rolled out that flag when a patient is on multiple generics that could be combined. By 2030, experts predict unmonitored de facto combinations will drop by 60% as tech catches up.

For now, though, the choice is yours - and your doctor’s. De facto combinations aren’t inherently wrong. But they’re not risk-free. They’re a workaround with real consequences. The goal isn’t to eliminate them - it’s to use them wisely, with awareness, support, and oversight.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 5, 2026 AT 05:30Demetria Morris

February 5, 2026 AT 15:15Geri Rogers

February 6, 2026 AT 12:52Samuel Bradway

February 7, 2026 AT 05:29Caleb Sutton

February 8, 2026 AT 12:51Jamillah Rodriguez

February 9, 2026 AT 12:50Susheel Sharma

February 10, 2026 AT 10:08Roshan Gudhe

February 11, 2026 AT 04:43Rachel Kipps

February 12, 2026 AT 23:09Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 13, 2026 AT 04:55Wendy Lamb

February 13, 2026 AT 11:21Antwonette Robinson

February 15, 2026 AT 02:27Ed Mackey

February 15, 2026 AT 02:57