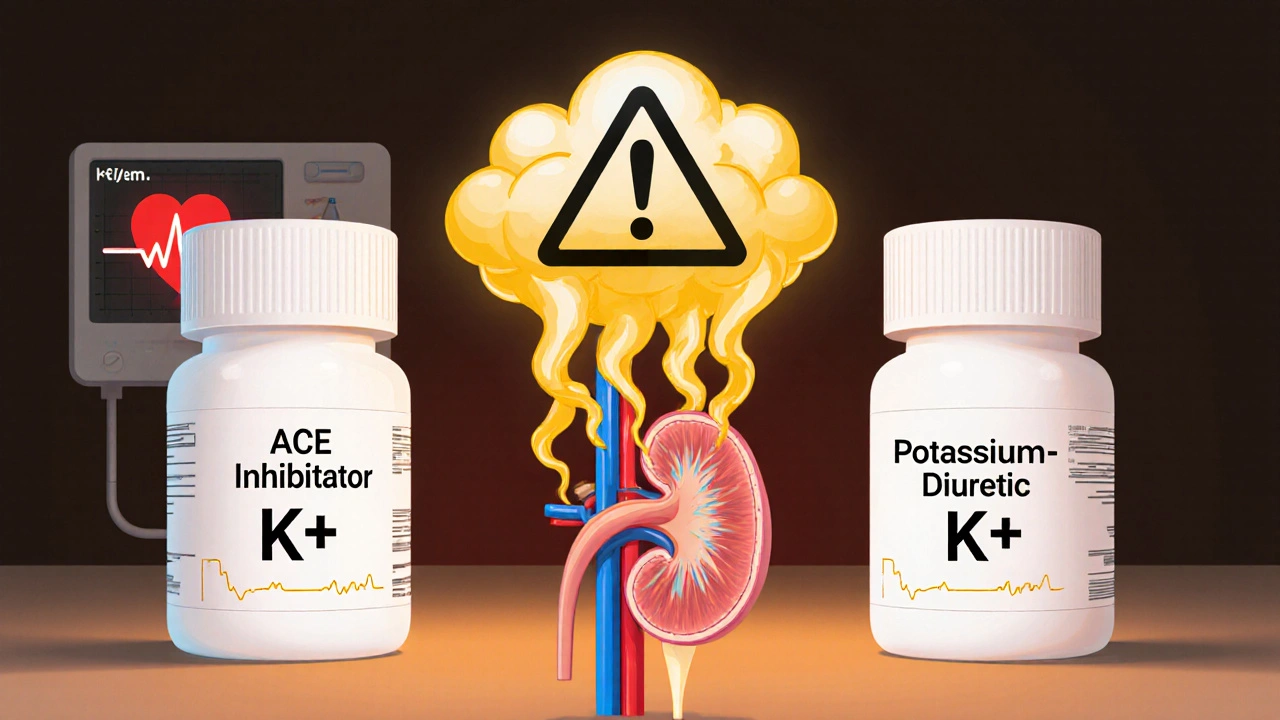

When you take an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure or heart failure, and your doctor adds a potassium-sparing diuretic to help with fluid retention, it might seem like a smart combo. But here’s the catch: ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics together can push your potassium levels dangerously high - a condition called hyperkalemia. This isn’t just a lab result. It’s a silent threat that can trigger irregular heartbeats, cardiac arrest, or even death if ignored.

How ACE Inhibitors and Potassium-Sparing Diuretics Work

ACE inhibitors - like lisinopril, enalapril, or ramipril - block a hormone called angiotensin II. That helps relax blood vessels and lower blood pressure. But there’s a side effect you might not know about: less angiotensin II means less aldosterone. Aldosterone is the hormone that tells your kidneys to get rid of potassium. When it drops, potassium builds up.

Potassium-sparing diuretics - such as spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, or triamterene - do something similar but in a different way. They stop your kidneys from reabsorbing sodium, which pulls water out of your body. But unlike other diuretics (like furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide), they don’t let potassium go with it. In fact, they actively hold onto it.

Put them together, and you’ve got a double hit on potassium excretion. One drug cuts the signal to flush potassium out. The other physically blocks the channel that lets it leave. The result? Potassium piles up in your blood.

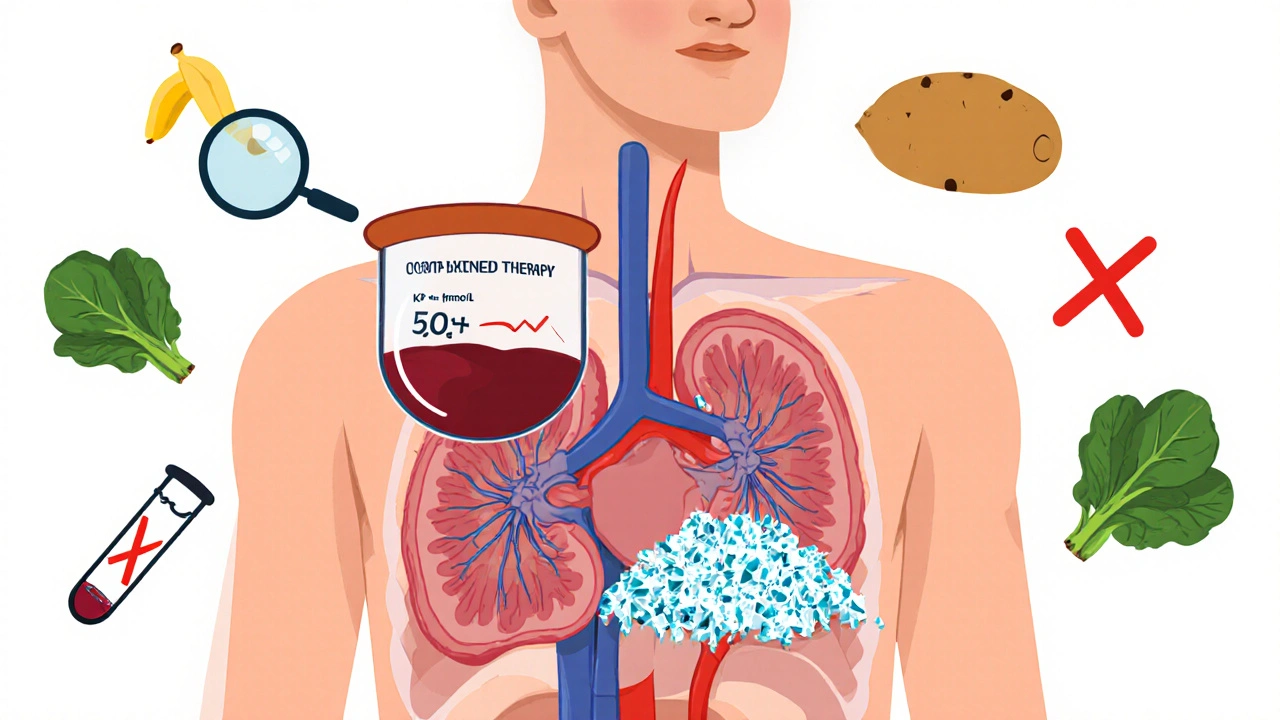

What Is Hyperkalemia - And Why It’s Dangerous

Hyperkalemia means your blood potassium level is above 5.0 mmol/L. Normal is 3.5 to 5.0. When it hits 6.0 or higher, your heart’s electrical system starts to misfire. You might not feel anything at first. No chest pain. No dizziness. That’s why it’s so sneaky.

But then - boom - your heartbeat goes chaotic. Ventricular fibrillation. Cardiac arrest. That’s not theoretical. Studies show that people with potassium above 6.0 mmol/L have a 1 in 5 chance of dying within 24 hours if it’s not treated. And this isn’t rare. In one study of 1,818 patients on ACE inhibitors, 11% developed hyperkalemia. When you add a potassium-sparing diuretic? The risk jumps 3 to 5 times higher.

Who’s Most at Risk

Not everyone on this combo will get high potassium. But some people are sitting ducks. The biggest risk factors:

- Chronic kidney disease (eGFR below 60 mL/min)

- Diabetes

- Heart failure

- Age over 65

- Already having a potassium level above 4.5 mmol/L before starting the combo

If you have two or more of these, your risk isn’t just higher - it’s severe. The Cleveland Clinic uses a simple scoring system: 2 points for low kidney function, 2 points for high baseline potassium, 1 point each for diabetes or heart failure, and 2 more if you’re on a potassium-sparing drug. Score 4 or higher? You’re in the danger zone.

And here’s something most people don’t realize: the biggest spike in potassium happens in the first 3 months. Peak risk? Weeks 4 to 6. That’s when most hospitalizations happen.

The Numbers Don’t Lie - Real Data on Risk

Let’s look at real-world data:

- ACE inhibitors alone: 11% risk of hyperkalemia

- ACE inhibitor + spironolactone: 18.7% risk (REIN study)

- Patients with eGFR under 30 on this combo: up to 19.7% risk

- Thiazide or loop diuretics (like furosemide) reduce hyperkalemia risk by 34%

- ARBs (like losartan) cause about 18% less hyperkalemia than ACE inhibitors

And the cost? Hyperkalemia-related hospitalizations in the U.S. cost $4.8 billion a year. Each episode averages over $11,000. That’s not just a medical problem - it’s a financial one too.

What You Should Do - A Practical Guide

If you’re on this combo, here’s what you need to do - not what your doctor *might* do, but what you should insist on:

- Get your potassium checked before starting. If it’s above 4.5, ask if this combo is really safe.

- Test again at 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks after starting. Don’t wait for your next routine visit.

- After 3 months, test every 3 to 6 months. If your kidney function is poor, test monthly.

- Know your numbers. If potassium hits 5.1, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait for 6.0.

If your potassium rises above 5.0, don’t panic - but don’t ignore it either. Here’s what your doctor should consider:

- Reduce the ACE inhibitor dose by 50% and retest in 1-2 weeks.

- Add a thiazide diuretic like hydrochlorothiazide (12.5-25 mg daily). This can drop potassium by 0.5-1.0 mmol/L in two weeks.

- Switch from spironolactone to triamterene - it’s weaker and less likely to cause spikes.

- Consider switching from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB - slightly lower risk.

Diet Matters - More Than You Think

You might think, “I eat healthy - I’m not eating salt.” But healthy doesn’t mean low in potassium. Bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, beans, yogurt, and even salt substitutes (like NoSalt or Lite Salt) are packed with potassium.

One banana has 420 mg. One baked potato? 900 mg. A cup of spinach? 840 mg. The average American eats 3,000-4,000 mg a day. For someone on this combo, that’s too much. Experts recommend keeping intake under 50-75 mmol per day (about 2,000-3,000 mg).

And here’s the kicker: many processed foods have hidden potassium additives. Things like “potassium chloride” or “potassium phosphate” in canned soups, protein bars, and sports drinks. Read labels. If you see “potassium” on the ingredient list, avoid it.

Studies show that just cutting dietary potassium can lower your blood levels by 0.3-0.6 mmol/L. That’s the difference between a warning and a crisis.

New Tools - And Why They’re Game-Changers

There’s new hope. In 2022, the FDA approved two new drugs: patiromer (Veltassa) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma). These aren’t diuretics. They’re potassium binders. They grab excess potassium in your gut and flush it out in your stool.

They’re not magic. But they let people stay on life-saving ACE inhibitors and spironolactone without risking death. In trials, 89% of patients who couldn’t tolerate the combo before were able to restart it after using these binders.

And there’s more. The DAPA-CKD trial showed that adding dapagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor for diabetes) reduced hyperkalemia risk by 32% in patients on ACE inhibitors. That’s a triple therapy: ACE inhibitor + spironolactone + SGLT2 inhibitor - and it’s safer than you’d think.

Even digital tools help. Apps that track your daily potassium intake have been shown to cut hyperkalemia episodes by 27%. If you’re serious about staying safe, download one.

Why Doctors Often Get This Wrong

Here’s the ugly truth: even though guidelines say to monitor potassium within 1-2 weeks of starting this combo, only 57% of patients actually get retested within 30 days. And 33% of those with potassium above 6.0 - the level that can kill - had no follow-up within a week.

Why? Doctors are afraid. They know these drugs save lives. A heart failure patient on ACE inhibitors and spironolactone has a 23% lower chance of dying. So when potassium rises, they hesitate. They don’t want to take away the good for fear of the bad.

But that’s the wrong trade-off. You don’t have to choose between safety and survival. You can have both - if you monitor, adjust, and use new tools.

Only 28% of primary care doctors feel confident managing hyperkalemia. That’s why so many patients slip through the cracks. You can’t wait for your doctor to be perfect. You need to be your own advocate.

What to Do Right Now

If you’re on an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic:

- Check your last potassium level. If you don’t know it, call your pharmacy or doctor.

- If it’s above 4.5, ask if you need a more frequent test schedule.

- Review your diet. Are you eating bananas every day? Potatoes with dinner? Salt substitute? Cut them out for two weeks and see what happens.

- Ask if a potassium binder like Lokelma or Veltassa is right for you.

- Don’t stop your meds without talking to your doctor - but don’t stay silent if your numbers are rising.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about control. You’re not powerless. You have choices. You have data. You have tools. Use them.

Can I still take ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics together?

Yes - but only under close monitoring. This combination is often necessary for heart failure or kidney disease. The key is regular potassium testing, dose adjustments, and possibly adding a thiazide diuretic or potassium binder to offset the risk. Never stop these medications without talking to your doctor.

What are the symptoms of high potassium?

Many people have no symptoms at all until it’s severe. When symptoms do appear, they include muscle weakness, fatigue, numbness, nausea, irregular heartbeat, or chest pain. But because symptoms are often absent, blood tests are the only reliable way to detect it.

How often should I get my potassium checked?

If you’re at high risk (eGFR under 60, diabetes, heart failure), check within 1 week of starting the combo, then again at 2 and 4 weeks. After that, every 3 months. If your kidney function is below 30, check monthly for the first 3 months. If you’re low risk (eGFR over 60, no diabetes), testing every 6-12 months may be enough.

Can I replace potassium-sparing diuretics with something safer?

Yes. If you’re on spironolactone or eplerenone and have high potassium, your doctor might switch you to a thiazide (like hydrochlorothiazide) or loop diuretic (like furosemide). These lower potassium and help with fluid. They’re safer in combination with ACE inhibitors. But they’re not always an option - especially if you have heart failure. Talk to your doctor about alternatives.

Are there foods I should avoid completely?

Avoid or limit: bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, avocados, beans, yogurt, salt substitutes (NoSalt, Lite Salt), and processed foods with potassium chloride or potassium phosphate. Aim for under 3,000 mg of potassium per day. Use apps or food databases to track intake - most people don’t realize how much potassium is in healthy foods.

What if my potassium is high but I need these drugs?

New medications like Lokelma and Veltassa bind potassium in your gut and let you keep taking your heart and kidney meds safely. These are approved for exactly this situation. Ask your doctor if you’re a candidate. Many patients who thought they had to stop their life-saving drugs can now stay on them with these binders.

Final Thought: You’re Not Alone

This isn’t a mistake. It’s a known, predictable, and manageable risk. Millions of people take this combo safely every day. The difference? They know their numbers. They watch their diet. They ask questions. You can too.

High potassium doesn’t have to mean stopping your meds. It means being smarter about them.

Zac Gray

November 20, 2025 AT 10:39So let me get this straight - we’re giving people two drugs that each individually make potassium climb like a squirrel on a power line, then acting surprised when their heart starts doing the cha-cha? And the solution is… more blood tests? Cool. I’m sure the ER staff loves that. At least we’ve got apps now to track how many bananas you ate before your potassium turned into a death sentence. Progress, I guess.

Steve and Charlie Maidment

November 20, 2025 AT 15:25Look, I get it. Doctors are scared of stopping meds that ‘save lives.’ But here’s the thing - if your patient’s potassium hits 6.0 and you don’t react like your house is on fire, you’re not a doctor, you’re a liability. I’ve seen it. Guy was on lisinopril and spironolactone. Said he felt ‘a little tired.’ Two days later, code blue. No warning. No symptoms. Just… gone. Why are we still pretending this is ‘manageable’ when the data screams ‘danger zone’?

Michael Petesch

November 21, 2025 AT 23:43While the clinical implications of this pharmacological interaction are well-documented, one might reasonably inquire as to whether cultural or socioeconomic factors influence adherence to potassium monitoring protocols. In populations with limited access to routine laboratory services, the recommended testing schedule becomes, in practice, aspirational rather than actionable. This raises ethical concerns regarding equitable care delivery, particularly in rural and underserved communities where the burden of cardiovascular disease is disproportionately high.

Ellen Calnan

November 22, 2025 AT 07:25I had a friend who was on this combo. She didn’t even know she was at risk until she passed out in the grocery store. No chest pain. No warning. Just… black. Turns out her potassium was 6.8. They had to shock her twice. She’s fine now - but she doesn’t eat a single banana anymore. Not even in smoothies. She carries a little card in her wallet that says ‘I’m on ACE + spironolactone - check my K+.’ I cried when she told me. This isn’t just medicine. It’s survival. And we’re all just one missed lab test away from tragedy.

Richard Risemberg

November 23, 2025 AT 23:57Man, this is the kind of post that makes you wanna hug your pharmacist. Seriously - the combo of ACE + potassium-sparing diuretic is like putting a flamethrower and a lit match in a closet and calling it ‘home improvement.’ But here’s the beautiful part: we’ve got tools now. Lokelma? Veltassa? SGLT2 inhibitors? These aren’t just fancy names - they’re lifelines. And if your doc hasn’t mentioned them, ask. Hard. Like, ‘I’m not leaving until you explain this’ hard. You’re not being annoying - you’re being alive.

Andrew Montandon

November 24, 2025 AT 20:36Let’s be real: if your potassium’s above 4.5 and you’re on this combo, you’re playing Russian roulette with your heart - and the gun’s loaded. But here’s the thing - most people don’t even know what ‘mmol/L’ means. So how are they supposed to advocate for themselves? We need better education - like, ‘here’s your potassium level, here’s what it means, here’s what you eat that’s killing you’ - not just a printed sheet with 12 fonts and a logo. And yes, apps help. I used one. Cut my intake by 30%. My K+ dropped 0.7. That’s not magic. That’s just paying attention.

Sam Reicks

November 25, 2025 AT 13:17they want you to think this is about potassium but its really about the pharma companies selling binders. they made the problem so you'd buy the fix. same with statins. same with antidepressants. they put you on the combo so you'd need lokelma. its all a scam. the real cause of heart failure is glyphosate and 5g. just stop taking all meds and eat raw garlic. youll be fine. i did. my k+ is 3.2. they cant prove otherwise. lol

Chuck Coffer

November 25, 2025 AT 21:46Oh, so now we’re blaming the patient for eating spinach? How quaint. The real issue is that doctors prescribe this combo like it’s a free sample at Costco. No thought. No follow-up. Just ‘here, take this, come back in 6 months.’ And then they’re shocked when someone ends up on a gurney? Spare me the ‘you should’ve monitored’ lecture. If you’re prescribing it, you’re responsible for watching it. End of story.

Marjorie Antoniou

November 26, 2025 AT 08:16I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been on this combo for three years. I thought I was doing everything right - until I read this. I hadn’t checked my potassium in 8 months. I called my doctor today. Got an appointment for tomorrow. I’m scared, but I’m not helpless anymore. This post didn’t scare me - it gave me power. Thank you.

Andrew Baggley

November 27, 2025 AT 16:30Look - I get it. It’s scary. But here’s the good news: you’re not alone. Millions of people are on this combo and thriving. Why? Because they know their numbers. They check their diet. They ask questions. You can too. It’s not about fear - it’s about awareness. And awareness? That’s the most powerful drug out there. Keep going. You’ve got this.

Frank Dahlmeyer

November 29, 2025 AT 01:08As someone who’s been managing heart failure for over a decade, I can tell you this: the moment I started tracking my potassium daily with an app and swapped my banana for a green apple, my hospital visits dropped by 70%. It’s not glamorous. It’s not sexy. But it’s real. And if you’re reading this, you’re already one step ahead of the 90% of people who just nod and take the pills. Keep going. You’re doing better than you think.

Codie Wagers

November 30, 2025 AT 05:51The notion that hyperkalemia is a ‘manageable’ risk is a dangerous illusion propagated by a medical-industrial complex that profits from chronic disease. The true solution lies not in binders, apps, or dietary restrictions - but in dismantling the systemic reliance on pharmacological band-aids. The body, when freed from artificial hormonal manipulation, possesses an innate capacity for homeostasis. Why do we persist in pathologizing nature?

Paige Lund

November 30, 2025 AT 19:15Wow. So much text. I’m just here for the banana ban.